People have lots of questions about forgiveness.

Rightfully so, considering Jesus explicitly says that our own forgiveness hinges on it. In Matthew 6:15, Jesus says “If you do not forgive others, then your Father will not forgive your transgressions.”

No exceptions. Full stop. If you don’t forgive other people, you should absolutely, without question, brutally expect God not to forgive you.

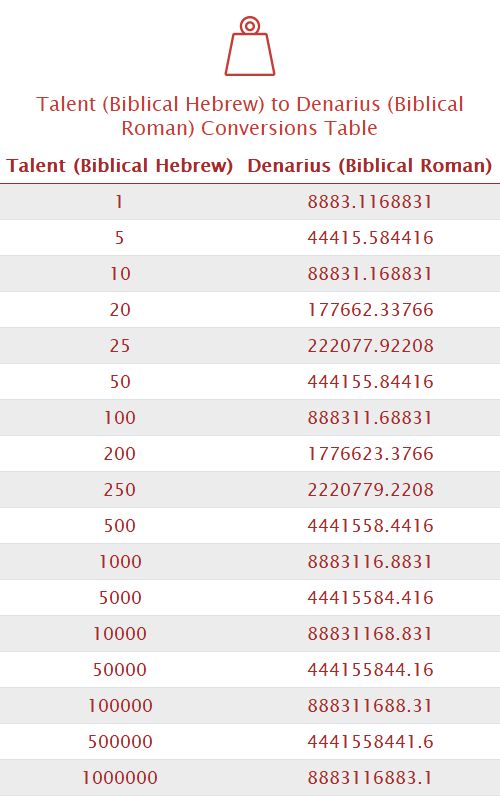

It makes sense though, doesn’t it? In the story of the unforgiving servant (Matthew 18:21-35), Jesus talks about two servants. One owes an enormous amount of money —- 10,000 talents, akin to several million dollars worth in today’s money.

The other owed about 100 denarii, or 1/60,000 of what the other slave owed.

That’s a massive difference.

In the story, the one who owes the massive debt is forgiven by his master, which is an enormous lesson in mercy. The first thing he does though, is find the one who owes him a pittance (by comparison), and choke him out until the guy promises to pay every last penny.

The lesson is clear: If you don’t extend grace to others, then you can’t expect Gods grace to be extended to you. Unforgiveness by us destroys any chance of unforgiveness by God.

But why?

What is the Biblical meaning of forgiveness?

Strictly speaking, forgiving is the ability to let go. It’s a deliberate decision to remove any sense of resentment, hatred, resentment, or revenge-seeking from your heart that you may have towards a person.

Or, at least, that’s the way that the Mayo Clinic summarizes it.

But truthfully, God looks at it the same way. Through the Cross, God is able to “let go” of the ways that we have sinned against Him. It doesn’t negate repentance, by any means (Luke 13:3, 5), but it does provide the mechanism by which true forgiveness can take place.

Think about it this way. The Bible speaks about our relationship with God as being a “covenant,” not a contract.

This matters more than you think. A “contract” is a legally-binding agreement between two parties. If one breaks the agreement, the other has the right — and some would say, the obligation — to render the contract null and void.

A covenant, on the other hand, is much more lenient. It allows for give and take because the relationship is based on trust and integrity. In a way, a covenant assumes that the agreement will be broken at some point, but the longsuffering of God allows a path for the perpetrator to return.

Biblical forgiveness relies on the covenantal relationship to keep peace between us and God, and us with us. It explains why Jesus Christ condemned the first debtor in Matthew 18 because of how he treated the second.

If he couldn’t appreciate what he was given by his own master, he judged himself unworthy of a gift like that.

Three practical questions about forgiveness

That’s all great, but we need to spend some time unpacking forgiveness? We know that we’re supposed to forgive, but how does that actually look in day to day life?

Generally, there are three questions I usually hear from people about this subject (including questions I have about it myself).

Does someone have to ask for forgiveness to be forgiven?

Here’s something worth remembering: Repentance is something they do, while forgiveness is something that you do.

Some would argue that you never have to forgive anyone that doesn’t ask for forgiveness. They claim that Peter’s question in Matthew 18 explicitly says, “how many times should my brother sin against me and ask for forgiveness and I still forgive him?” In their minds then, they must ask for forgiveness before I’m required to forgive them.

In some cases, this is true. When we ask for Gods forgiveness, repentance absolutely needs to be a part of that. Otherwise, it’s just empty words.

When dealing with each other though, the argument shifts a little. Why? Because we all know people that refuse to admit they were wrong — for anything. In doing so, it looks like they’re the epitome of strength, when, in reality, it just reveals an extremely fragile emotional state.

People that don’t ask for forgiveness can’t handle any kind of a blow to their ego. Their self-esteem is so terrible that admitting that they were wrong most likely will destroy them. To cover it, they convince themselves that they never actually did anything wrong, and twist real events to make it appear so.

Holding that grudge over people like that will only destroy you. Romans 12:18 should be your guiding light in this event: “If possible, so far as it depends on you, be at peace with all men.”

There are some people that you’ll never be able to be “at peace” with. The charge for us though is to at least try. If there can’t be any peace, we have to let go of that relationship and move on.

Does Matthew 5:23-24 really mean I shouldn’t worship until I’ve solved things with my brother?

Jesus says a lot of things that most people would consider extreme. But His statement in Matthew 5:23-24 about “leaving your offering at the altar” and having a reconcilation with your brother before continuing the sacrifice may be right up there.

For some, this means that you should never enter a worship service if there’s a disagreement between you and someone else. For others, it’s merely hyperbole about the urgency in healing relationships.

Both are right, in a way.

1 John 4:7-21 picks up this argument by arguing that “you cannot love God that you haven’t seen, and hate your brother whom you have seen.” The two can’t coexist.

The proof is in the pudding, in other words. The “test” of loving God is how you treat those who are created in His image.

Now, does that mean that you can’t worship if everyone hates you? I hope not, because right before Matthew 5:21-26, Christ Jesus says “blessed are those who are persecuted” (Matthew 5:11). If our worship to God depended on people’s opinions about us, none of us would be able to enter a church building — the Apostle Paul included.

If I’m being honest though, this passage may be the hardest thing you ever do in your walk with God. You will go through your share of temptations, but walking across the church building to make things right with your brother might be even scarier.

Doesn’t make it any less necessary.

How can I forgive when I still feel so angry?

Emotions are never a good barometer for our spiritual standing. We may feel one way, when the truth is actually something totally opposite.

If forgiveness of others is paramount to our own forgiveness though, how do I know I’ve forgiven others when it doesn’t feel like I have? After all, I’m still really angry about what happened — that must mean I haven’t actually forgiven them, right?

In the words of Jeremiah 17:9: “The heart is more deceitful than all else and is desperately sick; who can understand it?”

Be honest, our emotions are a terrible evaluator for what’s really going on. It leads us astray, lies to us, and makes us impulsive. Why should we trust it?

I understand the weight that such an emotion can carry, though. For that reason, I came up with a few questions that might help discern how you’re really feeling:

- Do I recognize their humanity? Psalm 103:14 tells us that God understands that “we are but dust.” The fact that we make mistakes forms part of the foundation for His forgiveness of us. But do we understand that about each other? Do we give each other the benefit of the doubt in our dealings too?

- Would I serve them? Not in a “Good Samaritan” way necessarily — as if they were broken down on the side of the road — but in a “washing the feet kind of way. Feel free to disagree with me, but one of the most remarkable parts of Jesus’ foot-washing scene in John 13 is the fact that He washed Judas’ feet. You know, the guy that would betray Him a few hours later. Would I humble myself before my enemy like that?

- Will I laugh when they suffer? Does their downfall bring me joy? This is different from the vindication that the saints felt in Revelation 6 while watching their persecutors be judged. I’m talking about taking pleasure in watching your enemies suffer. If so, we need to ask…why?

- Do I choose to relive the event? Or am I taking active steps to move past it so as not to re-anger myself?

- Do I have control? Those who withhold forgiveness like to say that they’re the ones in control, because they control the outcome of the situation. In reality, they’re not in control of anything — not even themselves. They are slaves to their emotions; however they feel about the situation governs their response. To be in control is to see it in a larger context: How does my forgiveness (or lack thereof) impact each others’ salvation?

Any more questions about forgiveness?

There are a lot more questions about forgiveness that someone could ask, but these are a few that should get you going. As you can tell, the concepts in Scripture are not just academic discussions, but real answers to everyday situations that you and I deal with on a regular basis.

Last modified: November 8, 2022