“Who is my neighbor?”

It’s less of a question and more of a desperate attempt to make himself look good, but the question is asked of Jesus nonetheless.

You could argue that the lawyer knew the answer all along. After all, Luke 10:25-37 clearly states that the man was trying to “justify himself.” In that case, Jesus could have just wiped the floor with his smugness.

Instead, Jesus flips the question by asking — at the end of the parable — which one of the men proved to be a neighbor.

It’s an extremely important point, because instead of simply answering the question by giving a list of approved individuals, Jesus challenges us to demonstrate our neighborliness to others every day.

In short, the question switches from “Who is my neighbor?” to “Am I a neighbor?”

Well…am I?

Our Neighbor is…Anyone

Humans are very clannish. We bring our people close, we exclude those we don’t like and/or those we perceive as threats. We take care of our own.

There is very little time left to tend to the needs of those we feel are outside that circle. After all, why should we waste valuable resources on people we don’t know when it doesn’t benefit us or our group?

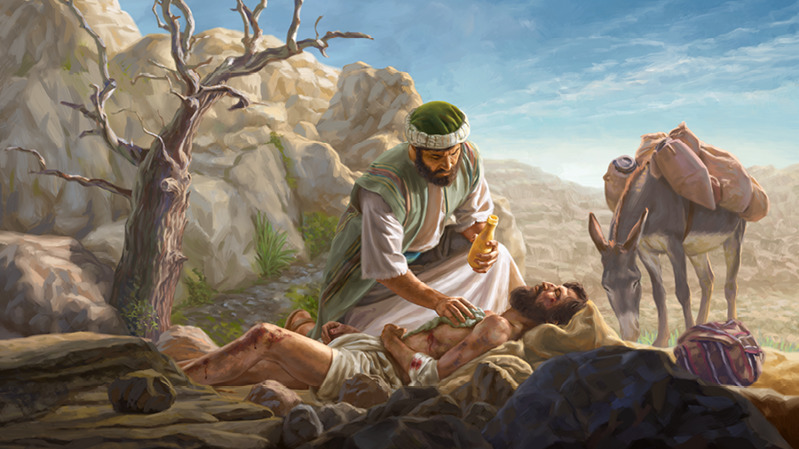

Yet that’s exactly what the Good Samaritan did in the eternally-famous parable of the same name. Of the three possible candidates — a priest, a levite, and a Samaritan — the latter was the least likely.

By using the Samaritan, Jesus proved a fundamental point about our lives. Our “neighbors” are not those we chose, but the ones that are in our immediate proximity on a regular basis.

They could be the people next door, or the ones we share a cubicle with. They might be those we sit in the break room, the people you coach little league with, or the guy that sits next to you in class.

They’re not “chosen” by anything except chance.

But that idea is important, because it limits our own biases in determining who we show kindness to. In this parable, Jesus argues that our “neighborly” spirit should be shown to all we come into contact with, regardless of who we or they are.

Our Neighbor is Anyone (Even Our Enemies)

Or, you could even say, especially our enemies.

This is a fact that the Apostles had to learn. After they watched Jesus’ rejection by a Samaritan city, they (respectfully) asked Jesus if they should ask God to burn the town to the ground.

Jesus was less enthusiastic in His response:

“You don’t know what kind of spirit you are of, for the Son of Man did not come to destroy men’s lives, but to save them.”

(Luke 9:56)

We highlight the second part of that verse (how Jesus came to “save men’s lives”) and hardly ever expound on the first. Yet it certainly deserves our attention.

In telling them that they “didn’t know” their own spirit, Jesus tells them that instead of operating out of love — as He was — they were operating from a defensive posture. The Samaritans had rejected Jesus! They needed to defend Him!

The same was true of King David’s men. When David (finally) was within striking distance, David’s men begged him to finally get rid of Saul once and for all.

David’s response echoes the same sentiment that Jesus had. “Far be it from me,” David argued, “that I should raise my hand against the Lord’s anointed.” (1 Samuel 26:6-12).

Did David have the right to kill Saul? Probably. The man had spent the better part of a decade chasing David through the wilderness.

Did Jesus have the right to kill the Samaritans? Probably. He was God, after all, and they not only rejected Him, but drove Him out of town. They rejected God, it’s only natural that God punishes them for it.

We all have enemies; that much is sure. Even David and Jesus had enemies.

But how we treat them should be the same as we do our friends (Compare Deuteronomy 22:1-4 and Exodus 23:4-9).

They’re still our neighbors, whether we like it or not.

Our Neighbor is Anyone (Even Our Enemies) That We Can Show Love To

The scene of a man left for dead on the road to Jericho was (unfortunately) all too common in those days. The area was known for its jagged rocks and drastic elevation changes — perfect conditions for thieves to make their home.

As such, this wouldn’t have been the first or the last time that these people would have had the opportunity to “prove” themselves a neighbor.

That may answer the real question of why the priest and the Levite didn’t stop. They had probably seen something like that before, so why stop now?

They have lives just like the rest of us, so you OBVIOUSLY can’t stop to help someone who’s dying on the side of the road. There’ll be another one there tomorrow, anyways. (Note the heavy sarcasm).

Alternatively, some have speculated that the reason they didn’t stop was because touching someone who was dead (even though he was still very much alive), became a matter of ritual purity.

Even if that were the case though, the law of caring for your brother would have overridden that fact. The man was dyyyyiiiinnnnngggg. Let’s not forget that little fact.

Regardless, they knew what God wanted them to do. It was stated multiple times throughout the Law and Prophets (Isaiah 58:6-14).

The only real reason that they chose not to help him because they just didn’t want to. It doesn’t need to be more complicated than that.

What Would You Have Done?

After Jesus’ asks the question about which one proved to be the neighbor, the man’s self-justifying stance is dropped. The only answer one can provide is the one that he gives: The Samaritan proved to be the neighbor, despite who should have been his neighbor.

With that, Jesus tells them to “go and do likewise.”

It shouldn’t matter who we “should” show kindness to, or who we “should” be a neighbor to. The reality is that every time we have an opportunity to be a neighbor, we should take it. It’s a state of mind, not a code of conduct governed by cultural laws.

Although, let’s admit it, that’d probably be easier.

Last modified: December 8, 2022